The Secret Life of Colour Part 1 - Ancient & Sacred

“Discover the secret history of ultramarine, vermilion, and ochre — ancient pigments that shaped art, culture, and creativity for centuries.”

The Secret Life of Colour – Part 1: Ancient & Sacred Pigments

Have you ever stopped to wonder where the colours in your pastel box actually come from?

We take it for granted that we can pick up a rich ultramarine stick or a warm earthy ochre whenever we like. But behind every pigment is a story — sometimes magical, sometimes dangerous, sometimes downright strange.

In this series, The Secret Life of Colour, I’m exploring the history, symbolism, and science behind some of the world’s most important pigments. Today we’ll start with three ancient and sacred colours: Ultramarine Blue, Vermilion Red, and Ochre.

🌌 Ultramarine Blue – The Heavenly Colour

For centuries, ultramarine was the most precious colour an artist could use — worth more than gold. It was made by grinding up the gemstone lapis lazuli, mined almost exclusively in Afghanistan. The process to extract the pure blue was incredibly labour-intensive: the crushed stone was mixed with wax and resins, then washed in lye to separate the rich blue particles from duller greys.

Because it was so costly, ultramarine was often reserved for the most sacred subjects in Christian art. The robes of the Virgin Mary were painted in ultramarine to symbolise holiness, humility, and purity. Patrons sometimes even included in contracts exactly how much ultramarine an artist had to use!

Famous Artists:

-

Michelangelo left parts of the Sistine Chapel unfinished when his patron couldn’t afford enough ultramarine.

-

Vermeer used it lavishly in works like Girl with a Pearl Earring, even though it nearly bankrupted him.

Today, thankfully, we don’t have to crush gemstones. Synthetic ultramarine, invented in 1828, is chemically identical to the real thing — affordable, safe, and still carrying that velvety, spiritual depth.

🔥 Vermilion Red – Bold but Deadly

If ultramarine symbolised the divine, vermilion was the colour of power and vitality. It was made from cinnabar, a mineral form of mercury sulphide. The Romans painted their murals with it, Chinese artisans used it in lacquerware and imperial seals, and medieval scribes illuminated manuscripts with its fiery glow.

But there was a dark side. Grinding cinnabar released toxic mercury vapours. Alchemists later discovered how to heat mercury and sulphur together to produce synthetic vermilion — brighter, yes, but still dangerously poisonous. Over time, many paintings darkened as vermilion slowly converted to a black form of mercury sulphide.

Symbolism:

-

In Rome, generals even painted their faces with vermilion during victory parades.

-

In China, it represented life, luck, and immortality.

Today, true vermilion is rarely used. Artists rely on safer cadmium reds and modern synthetics, which give us the same intensity without the deadly risk.

🌍 Ochre – The Oldest Pigment

Long before ultramarine or vermilion, there was ochre. This simple pigment — iron oxide mixed with clay — is humanity’s first paint. Archaeologists have found it in caves over 100,000 years old, used to paint animals, human hands, and stories on rock walls.

To make it, ancient people dug ochre earth, dried it, ground it into powder, and mixed it with binders like fat or spit. Its shades vary: yellow from goethite, red from hematite, brown from umber.

Why it matters:

-

Ochre is non-toxic, stable, and lightfast. Those cave paintings survive today because ochre simply doesn’t fade.

-

It’s deeply symbolic of connection to land and ancestry. Indigenous cultures worldwide still use ochres for ceremony and art, linking us back to the very first artists.

Even now, ochres are still mined naturally and sold in art stores — one of the few pigments you can use almost exactly as our ancestors did.

👀 Bonus Fact: The Mummy Paint

And here’s one of the strangest pigment stories of all. In the 1800s, you could actually buy a paint called Mummy Brown. Yes, it was literally made by grinding up Egyptian mummies — both human and cat — mixed with resins and oils.

Artists liked its transparent brown tone, but once they discovered what it was really made from, many abandoned it in horror. Edward Burne-Jones even claimed he buried his tube of Mummy Brown in the garden when he found out.

It’s often confused with Caput Mortuum (which means “Dead Head”), another earthy violet-brown pigment. But Caput Mortuum is just an iron oxide — safe and stable — while Mummy Brown thankfully disappeared as soon as the supply of mummies (mercifully) ran out.

✨ The Bigger Picture

Ultramarine carries spirituality, vermilion carries passion and danger, ochre carries the earth and our shared ancestry — and mummy brown reminds us that the history of art materials is stranger than fiction.

Every time you pick up a pastel stick, you’re not just colouring a page — you’re holding centuries of science, culture, and human history in your hand.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll explore Dangerous & Dazzling Colours — pigments so bright they transformed painting forever, but at terrible cost to the artists who used them.

👉 Want to explore colour, art techniques, and confidence in your own work? Come and join me inside The Creative Barn — my online art membership where we paint together, share stories, and grow as artists in a supportive community.

Want to learn about Soft Pastels?

Click on the button to register and get instant access to the free Pastel Basics for Beginners workshop.

Listen as I walk you through the essentials supplies needed to get started in Pastel painting.

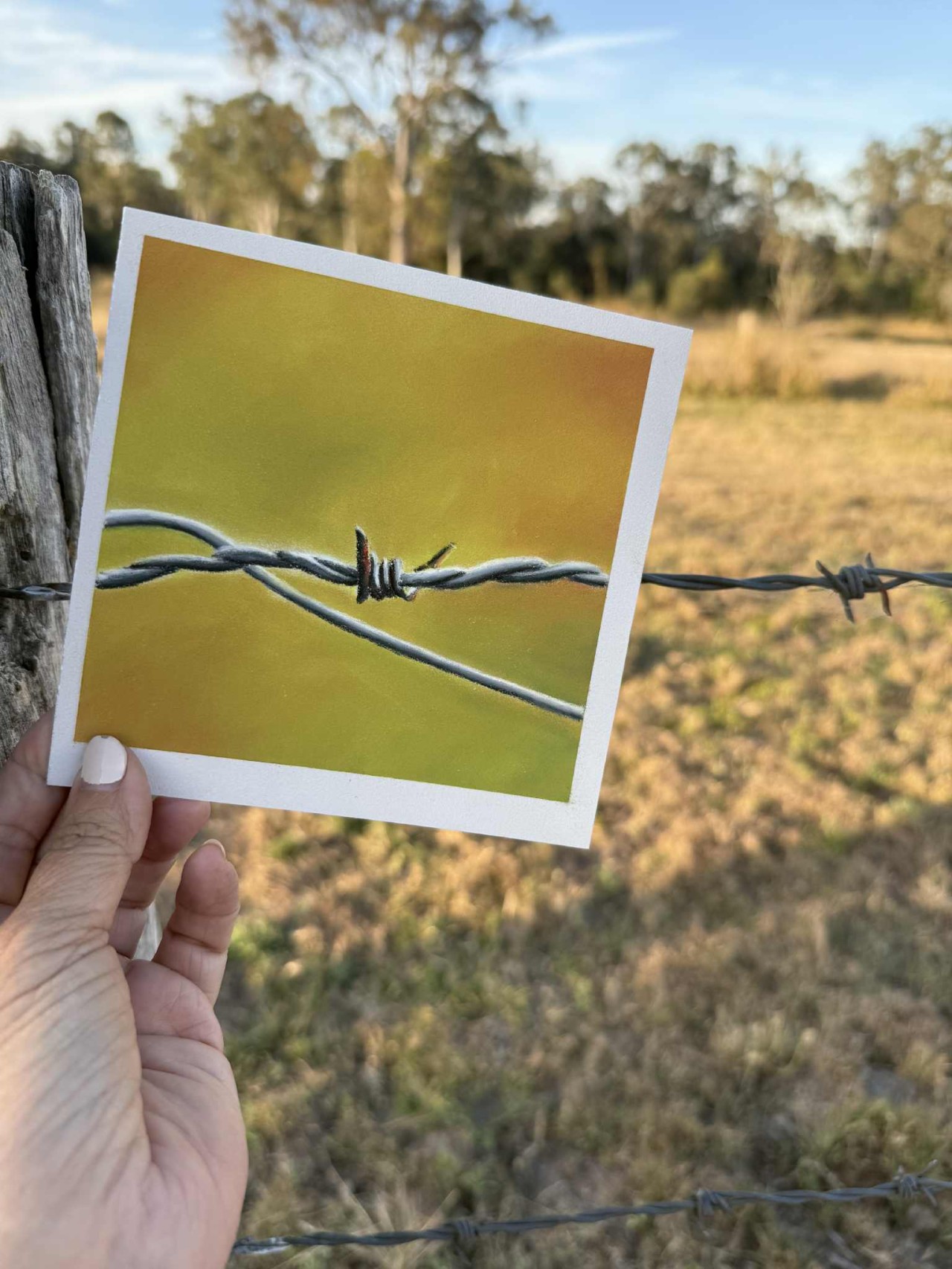

I teach you how to create this little barbed wire piece during the class. Everything you need is in the PDF workbook you'll receive when you register.

Kerri Dixon

Kerri Dixon